The Pap smear is a screening test that detects abnormal cervical cells, both squamous and glandular cells. It is a long-established, proven, and very successful screening tool for cervical cancer.

The HPV test screens for HPV, a sexually transmitted infection (STI) that affects squamous cervical cells. It is not a screening tool for glandular cell cervical cancer (adenocarcinoma), a more aggressive form of cervical cancer.

Cervical Cancer Screening in Australia

Radical and sweeping changes were made to the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP) in December 2017 with the Pap smear being replaced by the HPV test (a test for human papillomarvirus).

The NCSP outlines how and when cervical cancer screenings take place and, more importantly, whether and which types of cancer will be detected.

Introduced in 1991, the NCSP offered routine biennial Pap smear screening for all women aged 18-69 years. The program was great public health success story, with both the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer being halved to one of the lowest in the world.

This was achieved by using 2-yearly Pap tests to detect precanercous changes to cervical cells, allowing treatment before any progression to cervical cancer. Integral to this success was the support of a network of high-quality cytology services and registers. This resulted in the NCSP being world renown and the envy of many countries.

This has now been overturned and since December 2017 the HPV test has replaced the Pap smear as the frontline cervical screening tool.

Now when you have a 'Cervical Screening Test' (CST), you are not having a Pap smear but a HPV. A Pap smear will only be offered if the HPV test is positive.

Not only has HPV testing being introduced for the first time as a public health screening strategy; it has fast-tracked to become the PRIMARY screening tool. This means a Pap smear (cytology) will only be subsidised by the Government under the Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS) if you first test positive to HPV.

Other concerning changes to the NCSP are that a CST is only offered at 5-yearly intervals (not 2-yearly); and only beginning at age 25 years (not 18 years).

Terminology has also changed with the Pap smear now called Liquid-Based Cytology (LBC).

This is a radical and fundamental change to the cervical cancer screening program. There is little regard for the empirical evidence and lessons learned from the 70+ years since the Pap smear test was developed; the 50+ years of organised cervical screening in Australia; and the 26 years of empirical evidence and reporting from the world-acclaimed NCSP.

Understanding the Reproductive-tract and Cancer

The aim of population cervical cancer screening programs directed specifically at asymptomatic women is to reduce the incidence of invasive cervical cancer. In order to understand why relying on the HPV vaccine and triage HPV testing is problematic, it is important to understand the types of cervical cancer. This information is a bit technical and complicated, but it is critically important for women to understand the differences to enable educated choices about reproductive health.

Two Types of Cervical Cancer

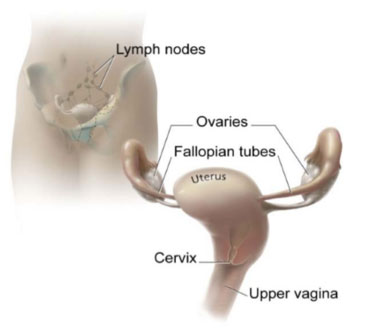

Cervical cancer affects the cells of the uterine cervix, which is the lower part (or ‘neck’) of the uterus where it joins the inner end of the vagina. It is where the Mullerian-derived glandular tissue from the upper genital tract meets the squamous tissue of the lower or outer genital tract.

The cervix and nearby organs

Source: National Cancer Institute <NCI Visuals Online> Illustrated by Don Bliss

Cancers of the upper genital tract (e.g. of the ovaries, Fallopian tubes and endometrium) are glandular cell cancers.

Cancer of the cervix can be either squamous or glandular.

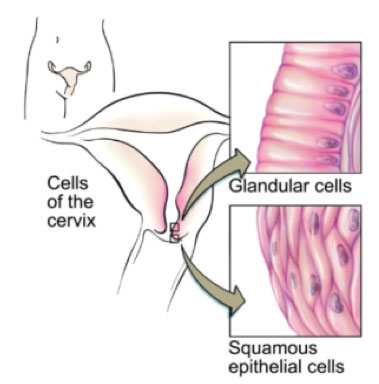

Cells of the Cervix

Source: National Cancer Institute <NCI Visuals Online> Illustrated by Don Bliss

There are two types of cervical cells – squamous and glandular. The Pap smear takes sample cells from the transformation zone of the cervix where the squamous cells and glandular cells meet. This is where most cervical abnormalities and cancer are detected as the cells are undergoing constant change.

The sample cells are then examined under a microscope for any abnormal (dysplastic) change. Any abnormalities are then classified and graded by the cytologist.

Squamous cell abnormalities and cancer

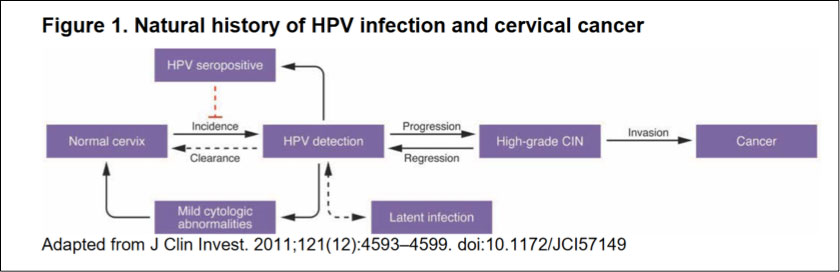

Any abnormal changes to cervical squamous cells typically have a long lead time, with several preliminary stages before invasive squamous cancer. It is not an inevitable linear progression as the vast majority of low-grade squamous abnormalities resolve without treatment. Even many high grade abnormalities may regress; if not, they can be treated by a range of procedures.

The terminology relating to the preliminary stages has changed and evolved over the years, but the following terms refer to squamous-cell abnormalities:

mild, moderate and severe dysplasia; cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN): CIN1,CIN2,CIN3; squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL); and squamous carcinoma in situ (SCIS)

It is critically important to realise that HPV infection relates ONLY to squamous cell abnormalities:

The papilloma viruses are attracted to and are able to live only in certain cells called squamous epithelial cells. These cells are found on the surface of the skin and on moist surfaces (called mucosal surfaces)...

Source: American Cancer Society

Glandular cell abnormalities and cancer

Like the glandular cancers of the upper genital tract, cervical glandular cell cancer (adenocarcinoma) is more aggressive and has a shorter lead time.

There are two precursors to (invasive) adenocarcinoma: atypical glandular cells and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS). In practice there is no ‘low grade’ glandular-cell abnormality, as any atypical change is referred for immediate colposcopic investigation and treatment.

The Pap smear

The Pap smear is named after Dr George Papanicolaou who developed the test in 1943. A sample of cells collected from the transformation zone of the cervix. With the conventional Pap smear, the cells are smeared onto a glass slide, stained and examined under a microscope for any abnormalities.

Liquid-Based Cytology (LBC) is a newer technology that involves a different method of preparing cervical samples for examination. The cells are placed in a vial containing preservative liquid. The sample is then sent to the laboratory for processing to remove obscuring material before being placed on a slide.

Any cell abnormalities (both squamous and glandular) detected on cytology are then classified and graded, as discussed above.

Hence the Pap smear can detect the early precursors of both types of cervical cancer.

The Pap smear became widely accepted as a very effective screening test for cervical cancer: In countries that had programs, morbidity and mortality from invasive squamous cell cancer was considerably reduced.

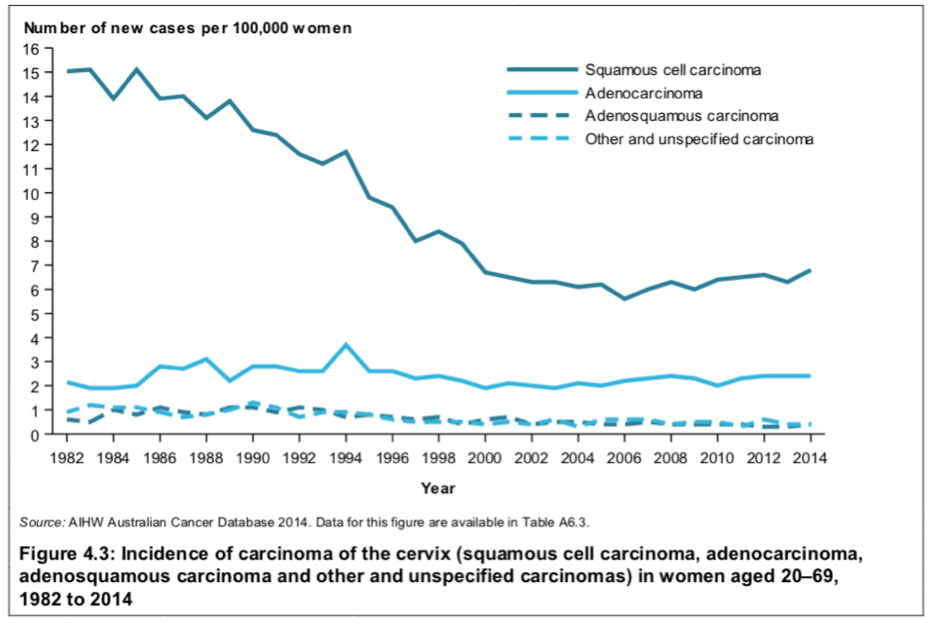

In Australia the incidence of squamous-cell cancer was more than halved between the years 1982-2014.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018

Figure 4.3 shows since around the year 2000, the relative incidence between squamous and glandular cancer has remained more or less constant at 70% and 30%, respectively.

Over the years the empirical data from the NCSP has show consistently that the biggest risk factor for cervical cancer is not having regular Pap smears.

HPV and HPV Testing

What is HPV?

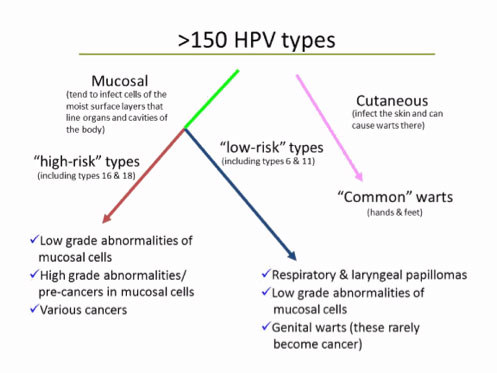

HPVs are a group of more than 150 related viruses. Each HPV virus in the group is given a number, which is called an HPV type or strain.

The papilloma viruses are attracted to and are able to live only in certain cells called squamous epithelial cells.

These cells are found on the surface of the skin, and on moist surfaces (called mucosal surfaces). Of the more than 150 known strains, about 75% HPV types are called cutaneous because they cause warts on the skin. The other 25% of the HPV types are mucosal types of HPV, and genital HPV types are in this group.

Source: American Cancer Society

Genital HPV is a very common sexually transmitted infection (STI). It is spread mainly through intimate direct skin-to-skin contact. It’s not spread in blood or other body fluids.

Genital HPVs are classified as

"low risk”: HPV types that tend to cause warts not cancer; or

“high risk”: oncogenic HPV types that have the potential to cause cancer.

Like any virus, genital HPVs continually evolve and mutate. In Australia of the 40 known genital HPV strains, 15 are considered oncogenic, with types 16, 18 and 45 being the most prevalent.

HPV is such a prevalent STI that it could be considered a normal part of being sexually active. Most people will have HPV at some time in their lives and never know it. It is asymptomatic. You may only become aware of HPV is you have an abnormal Pap smear result or if genital warts appear.

Although HPV infection is very common, in most people it clears up naturally in about 8-14 months. In a small number of women, the HPV stays in the cells of the cervix. When the infection is persistent, not cleared readily, there is an increased risk of developing squamous-cell, pre-cancerous abnormalities.

The HPV Test

In contrast to the Pap smear, the HPV test is not a test for cancer.

The actual procedure is identical to having a Pap smear: a scraping of cells is taken from the cervix and sent off for testing. However the sample is not sent to cytology but to a laboratory to undergo partial HPV genotyping to see if one or more oncogenic HPV types are present.

The HPV test is classified as one of the following: 'Oncogenic HPV not detected'; 'Oncogenic HPV 16/18 detected'; 'Oncogenic HPV (not 16/18) detected'; or 'Unsatifactory' [retest needed due to sample being inadequate].

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019

HPV and Primary Cause

In countries that don’t have Pap smear screening programs, the burden of invasive squamous cancer is great. The precursor CIN abnormalities cannot be detected and hence have the potential to progress to invasive cancer.

Studies in countries without screening programs resulted in the premise that HPV is the primary cause of squamous cancer: Infection with a persistent oncogenic HPV type is the necessary first step before any precancerous CINs can develop. And without Pap screening to detect these, the high-grade CINs go untreated and potentially become invasive cancer.

Source: Medical Services Advisory Committee (2014)

In developing countries without Pap smear screening programs, the HPV testing strategy made sense. Women who test positive to high risk HPV types can then be prioritised to access the limited health care resources such as cytology.

This strategy does not make sense, however, in countries like Australia with the world acclaimed NCSP, excellent cytology services and gynaecological care available - and where 30% of the invasive cervical cancers diagnosed are glandular-cell cancers.

HPV Test vs. Pap Smear

If HPV Tests Do Not Detect Cancer, Why Replace the Pap Smear?

An even better question is: Why would you have a Pap smear and not find out the result?

This is what is happening with the current system. A sample of cells is taken from the cervix and sent off for testing ... but not to cytology. It only reaches cytology if it passes the HPV test. If, and only if, it tests positive to certain oncogenic HPV types, the same specimen of cells is then reanalysed using reflex cytology.

Talk about confusing, complicated and time wasting!

In summary:

The Pap smear is a screening test that detects abnormal cervical cells, both squamous (CINs) and glandular (adenocarinoma). It is a long-established, very successful and proven screening tool for cervical cancer.

The HPV test screens for HPV, a sexually transmitted infection (STI) that affects squamous cervical cells. It is not a screening tool for glandular cell cervical cancer (adenocarcinoma), a more aggressive form of cervical cancer.

Here is some wisdom from the past:

Should I have a special test for HPV?

There is an HPV test available which can identify strains of HPV. This is not a test for cancer... Because most HPV infections usually resolved naturally, and there is no cure, there is little reason to have an HPV test...

While a Pap smear cannot identify which type of HPV is present, regular Pap smears will make sure any changes that occur are identified early and managed effectively.

Source: NCSP webpage, 2009

The Co-Test

One way around this mess is to have both tests (the HPV test and the LBC test) by requesting a Co-Test.

During the examination, two samples of cervical cells and taken and placed in two separate containers. One container is sent to cytology (LBC test), and the other to a laboratory for partial HPV genotyping (HPV test).

Good luck with navigating the NCSP!

DES Screening:

In recognition of the special screening needs of DES-exposed women, the NCSP Guidelines state they should be offered a co-test.

Recommendation 17.1 of the NCSP Guidelines states that DES-exposed women

"...should be offered an annual co-test and colposcopic examination of both the cervix and vagina indefinitely."