Over the following decades DES was marketed and prescribed for a bewildering and often contradictory range of conditions: to slow and prevent aging; to stop hot flushes and as treatment for other menopausal symptoms; to prevent miscarriage, for pregnancy maintenance, as a pregnancy “tonic”; as the oral contraceptive pill; as the ‘morning after’ contraceptive pill; to stunt the growth of tall girls; to suppress lactation; as a hormonal pregnancy test; to treat acne…

During pregnancy

Shortly after it was synthesised, DES was being touted as a treatment for late-pregnancy complications and for high risk pregnancies, such as women with diabetes. Let’s be very clear here: this was not based on any scientific research and DES did not prevent miscarriage. In fact it increased the risk of miscarriage and foetal death, and was subsequently used as the “morning-after” contraceptive pill.

Sir E. Charles Dodds, the co-developer of stilboestrol, was against the drug being given to healthy women, and he was particularly aghast when told it was being used to “prevent miscarriage”. He had published research in 1938 showing the drug actually prevented or ended pregnancies in rabbits and rats.

The Smiths of Boston

Dr George van Sichlen Smith (Head of the Ob/Gyn Department at Harvard Medical School, 1942-1967) and his wife Dr Olive Watkins Smith (a biochemist) theorised that the new drug would be of value in the treatment of impending miscarriage and late pregnancy complications. This was based on the earlier discovery that progesterone levels dropped prior to complications in pregnancy. They hypothesised that the administration of DES would be of therapeutic value because it was thought to upset and bypass the balancing effect of the pituitary gland and stimulate the body’s own production of progesterone.

“It was found, however, that diethylstilbestrol, unlike naturally occurring estrogens, was not depressed in its pituitary stimulating effects by the presence of progesterone and might theoretically, therefore, provide an ideal agent for preventing progesterone deficiency in pregnancy.” Smith and Smith (1941)

However they were soon promoting DES as a treatment to prevent miscarriage. That is, to be given prophylactically to women with a history of prior miscarriage or pregnancy complications. They published papers that detailed the “Smith regimen”, giving instructions on exact dosages of DES to be given. They encouraged any interested doctor reading the article to try out their new “wonder drug”. Pharmaceutical companies assisted the research, offering free trials of DES to interested physicians.

“The present study, a clinical evaluation of our concept concerning the action of diethylstilbestrol in human pregnancy, was started in the fall of 1943 and is still in progress…The writer would like to emphasize that the credit for the present contribution belongs to the 117 obstetricians who not only followed our recommendations but were willing to pool their results and send us a complete record of each treated case.”

OW Smith (1948)

Of course we don’t know how many other doctors, in the US and internationally, simply followed the directions given and prescribed the new wonder drug to their pregnant patients.

In 1949 there was a considerable shift, with DES suddenly being recommended as beneficial for any pregnancy. The Smiths presented THE INFLUENCE OF DIETHYLSTILBESTROL ON THE PROGRESS AND OUTCOME OF PREGNANCY AS BASED ON A COMPARISON OF TREATED AND UNTREATED PRIMIGRAVIDAS at the Annual Conference of the American Gynaecology Society of 1949.

In an attempt to be ‘scientific’ and they wanted the two study groups as homogenous as possible, so only first time mothers expecting a normal pregnancy were allowed in the ‘DES treatment’ and ‘untreated’ groups. Any high risk pregnancy (the very condition DES supposedly treated) was excluded from the study. This selection of ‘normal’ primigravidas as subjects was to have to affect the subsequent clinical use of DES. The subjective comments made by the authors, such as DES babies were healthier and stronger and that DES appeared to render normal gestations ‘more normal’, had far-reaching ramifications on how DES was prescribed.

There were criticisms of the methodology, particularly the fact there was no control group only an untreated comparison group. The controversy itself led to many more "experiments" being conducted on unsuspecting women attending hospital ante-natal clinics, not only in the United States but other countries including Britain and Australia.

The Dieckmann Study 1953

The largest of these subsequent studies DOES THE ADMINISTRATION OF DIETHYSTILBESTROL DURING PREGNANCY HAVE THERAPEUTIC VALUE? was conducted by Dr William DIeckmann and colleagues of the University of Chicago. This study is one of the first large-scale, prospective double-blind, randomised clinical trials (RCT) reported in medical literature, and involved 2,000 women attending the Chicago Lying-In Maternity Hospital. The findings of this study showed, to the surprise of the researchers, that the DES-treated group experienced higher rates of miscarriage, premature labour and neonatal death than the control group. The authors concluded that DES was no more effective at preventing miscarriage than bed rest. While they noted that the miscarriage rate was higher in the DES treated group than the control group, they concluded that “the total number of patients was too small to be statistically significant.”

A reanalysis of the data using modern statistical methods found that, although the women receiving DES were 1.8 times more likely to miscarry than the control group, this was not statistically significant simply because the overall sample size was too small. The number of subjects had been arbitrarily picked and, based on current statistical knowledge and criteria, it is now known a much larger sample size was required to handle the number of study variables and subset analyses.

DES as a pregnancy tonic

Despite the finding that DES did not prevent miscarriage, clinically the Dieckmann study was not influential as DES was already entrenched as standard obstetric clinical practice. The Smiths’ reaction to the Dieckmann study was to simply restate their conviction that DES reduced complications of pregnancy and had “saved many babies”. In a 1954 article they reaffirmed their belief that DES would even “make a normal pregnancy more normal” and recommended commencement of DES therapy as a prophylactic measure as soon as pregnancy was confirmed.

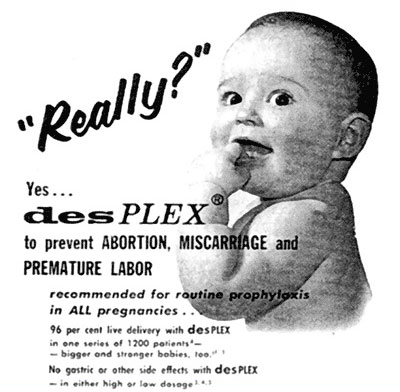

DES was being marketed as a ‘pregnancy tonic’, mixed with vitamins and recommended for all pregnancies. This 1957 advertisement for DesPLEX shows DES is now mixed with vitamins and minerals, and “recommended for routine prophylaxis in ALL pregnancies.”

In fact, many DES mothers believed they were taking vitamins.

DES was often imported, repackaged and re-branded. For example Diesavite, a very popular Australian brand that combined stilboestrol with vitamins and supplements, appears to be Australia’s version of DesPLEX. It contained a range of vitamins and minerals and, oh yes, 25 mg of stilboestrol.

So effective was the marketing to doctors of this ‘pregnancy tonic’ that many doctors didn’t realise that the drug contained stilboestrol and thought they were prescribing only vitamins.

To stunt the growth of tall girls

To treat young healthy prepubescent girls with a known carcinogen to stunt their adult height sounds like a bizarre science fiction experiment, but it is unfortunately true. This use was experimental and the efficacy and safety of this treatment was never proven.

The use of synthetic oestrogen hormones to stunt the growth of girls considered to be growing too tall, commenced as an experimental treatment in the 1950s in the USA. It was based on the observation that children with precocious puberty became short adults and had premature epiphyseal closure. The world’s first, largest clinical trial using DES (stilboestrol) commenced in Melbourne, Australia in 1959.

DES continued to be used as the oestogen of choice in this trial until 1972, when the paediatric endocrinologist conducting this ongoing trial changed the oestrogen hormone of choice to ethinyloestradiol due to concerns about cervical cancer linked to the daughters of women given DES to prevent miscarriage.

The rationale for this treatment was subjective, based on perceived notions that tall women would be excluded from careers such as classical ballet or airline hostess; have slouched posture due to trying to reduce their stature; suffer irritable and depressed personalities; have difficulty finding clothes and footwear that fitted; certain items of furniture would be uncomfortable and girls would be psychosocially withdrawn and experience problems with finding suitable partners when they got older.

Treatment was commenced at or prior to the onset of puberty. It entailed taking 3mg of Stilboestrol daily. When it became a concern that menstruation was very heavy, painful and lasted for several weeks a progesterin, Norethisterone, 5mg twice daily for the first four days of the month was introduced.

Later, in the 1970s, Ethinyloestradiol ( 25 times as potent as stilboestrol) was prescribed at a dose of 0.15 mg daily and Norethisterone 5mg twice daily for the first four days of the month.

The effect of taking the Stilboestrol (and Ethinyloestradiol) was to rapidly push the girl’s body into puberty. The oestrogen had the effect of fusing the epiphyses (growth plates) and thus inhibiting the growth of the long bones. This meant the rapid development of all secondary sexual characteristics.

This treatment was/is cosmetic. There was nothing medically wrong. These constitutionally tall girls were from tall families. However, medicalisation of their normal stature and subsequently, the use of powerful synthetic hormones to stunt their growth became almost mainstream within the medical profession, in an attempt to ensure these young women somehow fitted into the cultural and social expectations of the times. And it has had long term consequences.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT)

One of the first uses of DES in the 1940s was as a treatment of menopause, when this natural life stage was “medicalised”. Menopause became a "disease" of aging and menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes and night sweats were termed ‘oestrogen deficiency disease’. Oestrogen was seen as the "fountain of youth" and, by the mid-1960s, it was being recommended that all women go on oestrogen for the rest of their lives. Cancer rates among middle aged women soared and, in 1975, it was shown that oestrogen replacement therapy (ORT) was associated with increased rates of uterine cancer. Sales plummeted.

‘Unopposed oestrogen’ was touted as the culprit. It was maintained that the risk of cancer could be reduced by combining oestrogen with progesterone. This combined hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was heavily promoted, not only as a treatment of menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes and night sweats; but also as a treatment to prevent osteoporosis; to reduce the risk of heart disease; and to improve cognitive function and a general sense of well being.

There had never been any large-scale scientific studies to evaluate the efficacy and safety of HRT until the 1990s. And then, in July 2002, the largest of these scientific trials was abruptly and prematurely stopped when it was found that those women taking combined HRT had an increased risk of invasive breast cancer, ovarian cancer, heart attacks, blood clots and strokes.

Highly recommended reference is Barbara Seaman’s The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth (2003),

To suppress lactation

Many women were prescribed stilboestrol to dry up breast milk. Again, this was a very early use, dating from the early 1940s. Its safety and efficacy for this purpose have never been proven.

By 1970s the practice was widespread throughout Australia - the same time, incidentally, that DES was established as a proven carcinogen in humans. One nurse reported that the hospitals in Western Victoria “were awash with stilboestrol”

Stilboestrol was routinely prescribed if the mother had suffered a pregnancy loss or stillbirth. A number of our members have reported double exposures: DES mothers and DES daughters experiencing pregnancy loss or stillbirth were then administered stilboestrol for lactation suppression.

There were other cases where the mother, on becoming pregnant, was prescribed DES to wean a toddler. This of course meant that the foetus was exposed to DES.

Of concern to us is a number of our members subjected to this treatment have now developed breast cancer. This is probably not that surprising when you consider their situation is similar in many ways to DES mothers (exposed as adults around the time of pregnancy), and DES mothers have a statistically significant increased rate of breast cancer.

A dark side of this usage emerged during the 2012 Senate inquiry into Forced Adoption Practices. Young women, forced to give their child up for adoption, were administered DES to stop lactation and prevent them from breast feeding and bonding with the infant.

There has never been any research into the long term health effects or safety of this treatment.

Morning-after contraceptive pill

Perhaps the greatest irony to us is that that DES was prescribed to prevent pregnancy, to induce pregnancy loss. And this was known all along; back in 1938 Sir Charles Dodds reported that orally active oestrogen, including DES, interrupted early pregnancies in rabbit and rats

The safety and efficacy of DES as a post-coital “morning-after” contraceptive pill has never been proven. Given the treatment is administered before the woman knows she is pregnant, the efficacy is difficult to research. The “success” of the treatment may simply be the fact that the woman wasn’t pregnant in the first place. There has been no research or follow-up of the women receiving this treatment; or, if the treatment fails and the pregnancy continues, of the children exposed in utero to DES.

The morning-after pill was and is routinely given to sexual assault victims. One has to wonder at the wisdom of giving a massive dose of a known carcinogen and endocrine disruptor to young girls and women, particularly in a time of crisis when the immune system is possibly compromised.

Treatment of Acne in young girls and women

This appears to have been quite a common practice, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. There was no research or follow up of long-term adverse effects. Again, one has to question the wisdom of giving a potent hormone to young teenage girls at a time when their own hormone cycles are undergoing change and very susceptible to disruption.

Again, the Tall Girls experience has obvious parallels with this group of DES-exposed young women.